I remember it clearly. My mother taught at a school right off lower Third Avenue in NYC-- a major pawnshop area. In the spring of 1955 she came home and said, "I saw some banjos. Would you be interested in learning banjo?" Gad! I HATED banjo, but I was thinking of the plunka-plunka o the tenor banjo. Little did I know.

|

|---|

That summer, at a summer camp, I met Paul Prestopino and it all changed. Paul introduced me to the five string banjo, the Folkways Anthology of American Folk music series by Harry Smith, and the recordings of Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs.

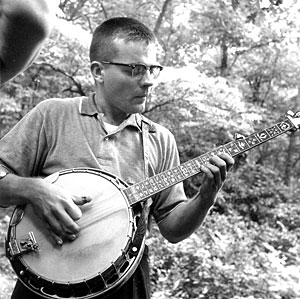

I came home, and bought a banjo-- a really cheap English one, as I recall. I started to hang out at Washington Square in NYC on Sundays where there was live folk music in the afternoon around the fountain. Within a few months I got to see the cream of the NYC crop of banjo players, both the bluegrass players-- Eric Weissberg, Marshall Brickman, Bob Yellin, Willie Dykeman, and Roger Sprung-- and the old-time players like Billy Faier, Luke Faust, Dick Weissman, John Cohen, and Tom Paley. I watched and watched and tried figuring it out when I got home-- generally with little success.

I plodded along playing "Pete Seeger" style for a while, and then I experienced the first "ah ha!" I was at a concert in New York one evening and Roger Sprung was there. I watched him carefully as he played "Cripple Creek." I noticed that his left hand was doing the same thing my left hand was doing when I played that song. It was then that I realized what I was looking for to get "Scruggs style" was all in the right hand-- it was a major revelation.

The next year I went down to the Swarthmore Folk Festival at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania. The headliner of the concert was Odetta. There was a lot of playing going on during the day and I got to see a great Bluegrass conglomerate with Mike Seeger, Paul Prestopino, Ralph Rinzler, Bob Yellin, and a few others.

On my return I went shopping for a better banjo and found an old Bacon and Day tenor banjo at Oreste Durante's shop on Park Row in Lower Manhattan. Old man Durante seemed to have a constant stream of good banjos coming in. I bought what I could afford. I then used my high school shop to fashion a new neck for it (a long-neck-- just like Pete Seeger's!).

|

|---|

By the next summer I was deeper into banjo, listening to the Folkways record of "American Banjo tunes, Scruggs Style." The neck I made, being my first attempt at such things, was inaccurately fretted and was warping. I took it off and made a standard length neck. This time I bought a Gibson fingerboard from Eddie Bell, the Gibson dealer in NYC. It was fretted accurately. I then found an old Vega resonator for the banjo, and I was on my way to playing three-finger style . I hung out at the Square, playing along to regular folk songs such as "Midnight Special" and "This Land is Your Land." I knew a few instrumentals, but never saw the three-finger style as a separate kind of music. At the time, it was all one: blues, bluegrass, folk. It was not unusual to see blues greats like Dave Van Ronk, playing along with "bluegrass bands" who were singing regular folk standards.

Then came my second epiphany. I was at the Sunday evening "hootenanny" that was held at the American Youth Hostel on 8th Street. Bob Yellin had just bought his first Gibson banjo (an RB 150-- graduating from an old Kay) and was sounding great. I was on my way out the door at about 10 at night (I had to get home by 11!) when the "Greenbriar Boys" (Yellin, Weissberg, Herald) started singing the Reno and Smiley classic "I Walked into a Church One Day." It stopped me in my tracks. Until then I had known the banjo as a way of playing instrumentals, but I never associated it with a "style." I was stunned by what I heard. I became a bluegrass convert.

Shortly after I had my third epiphany. I was invited to a party by Roger Sprung. While there he asked me if I'd like to try his banjo. It was the first time I had ever played a Gibson. It was like magic. The sound was right, and I was hearing stuff I never heard on my banjo. I needed one. Right now.

|

|---|

So I struggled along, saving money, and playing my old Bacon and Day. Along the way I got an old neck and matching pot and cobbled together a nice open backed banjo for more folkie stuff. But the dreams of a Gibson continued. While my fellow school mates doodled hot-rods in their notebooks, I doodled banjos and their inlay patterns.

In 1959 I began my training in Industrial Design at Pratt Institute. One of the exercises in English Class was to write a letter of appreciation to a public figure.

Every Thursday eve from 6:15 to 6:30 there was 15 minutes of bluegrass music on the Fordham University radio station. The program was called "Bluegrass Ramble" and was hosted by Bill Knowlton, a junior at the school. I wrote him a letter of appreciation.

Shortly after, he phoned and invited me to his place to listen to music. We became friends. One day he asked if I'd like to go along to an interview he was doing with Harry and Jeannie West.

Harry and Jeannie were transplanted southerners, living in the Bronx. Harry had an amazing record collection, and was also a collector and dealer of fine instruments. About a year earlier I had purchased a Dobro from him.

After Bill did the interview he asked if they would play a tune or two, and suggested I play banjo with them. Harry was unaware that I played banjo, and offered me the use of his Gibson RB-3.

The following week Harry phoned and said, in his long drawn out way, that he had enjoyed playing with me and I would be welcome to come by and play with them on any Saturday afternoon. I was in seventh heaven. And so began my first "band" experience.

|

|---|

Two things came from my association with Harry and Jeannie. The first was gaining the ability to improvise quickly and to anticipate changes in chords and timing. Harry and Jeannie's timing on some songs was, to say the least, unusual. The second was the acquisition of my first Gibson banjo.

The banjo was a pre-war RB-1 . An original 5-string. It had the oval "Mastertone" decal in the rim, but did not have a Mastertone tone ring. I set about to remedy that situation. I found a new Mastertone flat-head ring, and a new cast flange, since the original was bent and a few thinner parts had broken off. I decided to re-finish the banjo to a lighter color, thinking it would bring out the tiger-maple figure of the neck and resonator. Little did I know that the "tiger-striping" I was seeing under the dark finish had been painted on-- a common practice by Gibson on their less expensive models. First the dark came off, followed by the stripes. I was left with a banjo made from very plain, unfigured maple.

I had always wanted a gold-plated banjo, so I had all the parts plated before I re-assembled it. It played really well, and was a unique looker too!

|

|---|

The next summer, 1960, I drove down to the big festival at Asheville, North Carolina that was run by Bascom Lamar Lunsford. I got to play on stage with Harry and Jeannie and, with them, paid a visit to Bascom at his house.

Years later I was watching a documentary on PBS about Bascom and his festival. They had an interview with him at his house. I remarked to my girlfriend that I been there. She said, "Yeah," thinking I was talking about the Carolina area in general. So I fetched out the picture of me, Harry and Jeannie, and Bascom on his front lawn. "Wow! You were THERE!"

|

|---|

At the same festival I got to meet Bill Keith and Jim Rooney (who had traveled down from Boston), Bob Johnson , a great banjo player from Chattanooga, and Don and Ron Norman, two good banjo players from Georgia. It was a good trip.

The following year I went down again, and this time got to play on stage with Bayard Ray , a great mountain fiddler from Marshall, NC. He invited us back to his house after the show, and we spent four days with him-- the last house on the last road--

|

|---|

right up against the side of the mountain. There was no electricity, and no running water. The outhouse was a bit of a walk away, and we were told to take a stick to fend off snakes and to "watch for bears."

Before I had gone down I had worked for a bit with a cabinet maker in Connecticut. I had learned a lot about walnut in all its states of finish. So there I am, sitting in the outhouse and, looking around, realize it is made from walnut. I mentioned it to Bayard, who told me that his whole house (whitewashed on the outside) is walnut! "When my grandfather came here and built the house, he cut down the two largest trees he could find for the wood. They were walnut trees."

|

|---|

That same year (1961) was my first visit to the Indian Neck Folk Festival-- a "by invitation" festival sponsored by the folkies at Yale University and held at a big, old mansion on the Connecticut coast of Long Island Sound. It was three days of non-stop music with some of the best. EVERYONE was there-- Mark Spolstra, Dave Van Ronk, Reverend Gary Davis, Molly Scott, Carolyn Hester, Bob Dylan and many others. I did a great duet with Bill Keith where we played each other's banjos. Lots of fun!

|

|---|

I also met a bunch of bluegrass musicians in Connecticut , and traveled up regularly to play at monthly get-togethers.

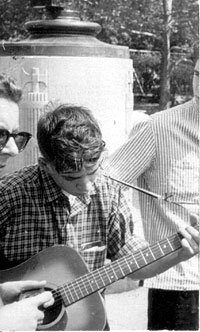

In 1959 I read a review of the Sunset Park banjo contest by Mike Seeger in "Gardyloo," and I decided to enter in 1960. It was quite a time. The contest was held every July 4th at Sunset Park in West Grove, PA, a grand old country music park set in farmlands about 40 miles south of Philadelphia on Route 1. It was a real eye opener. I had never been around that number of banjo players before, and many were really good. The contestants drew straws to determine the order. There were about 30 contestants. It was judged solely on audience applause. The first prize was a new Mastertone banjo. The winner for that year arrived late, so he played last. He was from North Carolina. Wish I remembered his name. A goodly bunch of players came up from the Galax, VA area including Charles Hawkes, Cullen Gaylen, and Ted Lundy . They were good, and they seemed to know it. Very intimidating.

|

|---|

The next year I tried again . This time I was a bit of a better player and got to the "run off" which was between me and Scotty Stoneman. Scotty could only play a few tunes on the banjo. It was only later that I found out what an amazing fiddle player he was. He was very drunk and was playing an old Mastertone whose tuning pegs were painted fluorescent pink. He poured his whole being into his playing, and he won the heart of the audience, and the contest.

I missed the 1962 contest, but I was there in 1963. By that time I had a new banjo and had figured a few things out about the contest. First, it didn't matter if you were a good banjo player or not. You had to "turn" the audience. The first person who did that, had a crack at winning. Second, you had to make it look hard-- got that from Scotty Stoneman. Third, the audience loved hearing the second string choked on the 10th fret. That sound was like waving a red flag at a bull.

I forget what I played, but I "worked" at it, and I found a place to make the 10th fret choke. It did the job. The audience cheered, and I had them. I won the Mastertone. On the way home, my girlfriend said, "Too bad they didn't know you could do the same thing if you were tied to a post." Yup. Nothing like a wiggle and a bit of showmanship. It certainly helped that I looked like an undernourished teenager too.

|

|---|

In the spring of 1962 my banjo was stolen from my parked car. I eventually found it in Silver and Horland, a music store on Park Row. I had a police "hold" put on it. I got it back about a year later after an unbelievable amount of paperwork. I had already received insurance money, so I sold it for the insurance company to Lowell Levinger, a banjo player from Boston who went by the name of "Banana." He later played guitar with Jesse Colin Young and the Youngbloods. The banjo was stolen from him about a year later and hasn't surfaced anywhere to my knowledge. I'd love to know who has it now.

While I was looking for a banjo, Harry West lent me his RB-3. Harry had a number of banjos for sale, but none of them appealed to me. I was offered a beautiful Argentine gray (almost green) RB-6 with gold sparkle binding. I sure have thought a lot about that banjo in the intervening years, but I just didn't like the feel of the neck. I was offered a nice RB-3 flat-head with a "wreath pattern" inlay, but I really wanted a gold plated banjo. That RB-3 I could have had for $400. I recently (2002) heard that Harry finally sold it for $35,000! My my!

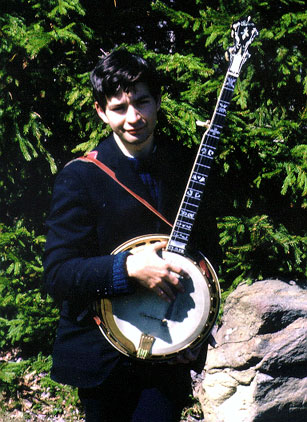

I finally bought a ball-bearing tenor Granada. I had played a ball-bearing that belonged to a friend of mine, and I really liked it, although they weren't as desirable as a flat-head. Harry contracted with Robbie Robinson, a banjo player from Ohio, to make the neck. I decided not to have an "original" neck made (hearts and flowers, with a fiddle peghead which said "mastertone" on it), but opted to have a "flying eagle" pattern a la Don Reno-- my old high school fantasy. It is the banjo I still have.

For more about my Granada, click here.

Continue -> Me and my old banjo - part 2